After 11 years of war in Syria, the COVID-19 pandemic, and an economic crisis, education for Syrian children and youth has been severely disrupted, leaving more than 2.4 million out of school. Failure by international governments to act urgently endangers the prospects of stabilizing Syria and facilitating recovery. Disruptions to education programming will have both immediate and long-term negative consequences for Syria's children and the country's future. Governments and donors must initiate a stronger push to facilitate a more sustainable and quality education response to help stabilize Syria and facilitate its recovery.

Overview of the Sector

Current Education Implementation in Syria

General and Cross-cutting Humanitarian Needs

Education Needs by Geographic Hub

Delays in Adopting an Early Recovery Approach to Education

Unsustainable Funding Approach

The Challenge of Data Management and Disaggregation per Region

The world’s attention has increasingly shifted away from Syria, as much of the country’s 11-year armed conflict has drawn down, the COVID-19 pandemic has become an enduring global reality, and other crises, like those in Yemen, Afghanistan, and now Ukraine, have come to the fore. Yet, an estimated 14.6 million vulnerable Syrians continue to face one of the most devastating humanitarian crises in the world. 1 A crucial component of the humanitarian response to this ongoing crisis involves the implementation of emergency education services, upon which approximately 6.1 million Syrian children and youth rely. 2 Systematic attacks on schools, forced displacement of students and teachers, and COVID-related disruptions have made it challenging for humanitarian organizations to ensure consistent access to education for Syrian children. Recent data show that 2.4 million children are out of school, 3 with many more at risk of dropping out. 4 Moreover, the United Nations estimates that effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will reverse nearly 20 years of progress in education completion around the world. 5 The implications of such global disruptions after more than a decade of war in Syria are especially bleak.

The impacts of these challenges on the education of Syrian children are varied and complex. Some of the long-term implications could entail reduced life expectancy and loss of human capital and economic productivity. The short-term effects of disrupted education on the safety and wellbeing of Syrian children are more immediately devastating: Loss of access to school too often leads to spikes in child labor, child marriage, and other major protection concerns. To make matters worse, humanitarian funding for the Syria crisis has declined amid intense competition for global aid. This sharp decline in education access and outcomes is a complete reversal from the pre-war potential of youth, who were once hailed throughout the region as a source of positive political, economic, and social change. Before the conflict, the country boasted a 98% attendance rate at the primary level and literacy rates at nearly 90% 6 for both men and women. 7 Today, a child born in the first year of the Syrian war will be approaching their 12th birthday and may have already missed several years of formal education, becoming part of the ever-growing “lost generation” of Syrians.

This analysis first provides an overview of the “education in emergencies” sector and its implementation in Syria, then examines the humanitarian needs of Syrians — particularly in regard to education — and, finally, explores the main challenges to effective education service delivery within the Syrian humanitarian response. Drawing on nine interviews with humanitarian practitioners across all of Syria’s geographic areas of operations, as well as a number of secondary U.N. and NGO reports, this analysis will provide recommendations to donor governments and their partners to address obstacles to effective education delivery in Syria and accelerate an early recovery approach. 8 Governments and donor agencies must recognize that education is a critical element of Syria’s eventual stabilization and sustainable recovery, and requires urgent action.

In any humanitarian crisis, education is often one of the first services to be disrupted and among the last to be restored. 9 The COVID-19 pandemic has caused “the largest disruption of education systems in history.” 10 The right to education is a fundamental right enshrined in international law, including the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), to which Syria is a signatory. Yet, it can be incredibly challenging to deliver in the midst of an emergency, with many risks involved, such as perpetuating conflict dynamics. Although education is often marginalized in overarching discussions on humanitarian needs, its role must not be underestimated. If implemented effectively, education can play a key role in helping societies engaged in protracted crises to emerge from war and to build back better.

In the early 2000s, education in emergencies (EiE) was conceptualized as a field of research and practice made up of those working to support education in crisis-affected and developing contexts. 11 This paved the way for the development and launch of the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) Minimum Standards for Education in 2004. 12 After activation of the cluster system 13 — a mechanism for coordinating delivery of services in a humanitarian context, led by the U.N. — advocacy efforts led to the inclusion of a cluster dedicated to education in 2007, re-affirming the importance of education services in humanitarian responses. 14 In an emergency, education interventions center on physical and psychosocial protection for children as a first step, ensuring schools are entry points for services, such as health and nutrition, and deliver life-saving messages to children (e.g., about health, hygiene, and disaster preparedness). Content focused on enhancing learning outcomes follows because children cannot learn until their physical and psychosocial needs are addressed.

After the initial emergency, global minimum standards advise that there should be a transition to the formal pre-crisis curricula, with the support of accelerated and catch-up curricula when needed. Unfortunately, the protracted nature of many conflicts we see today has placed learning in limbo with exclusively temporary measures to keep children learning. In ideal circumstances, when the initial emergency phase of a crisis has subsided, education programming calls for the adoption of an early recovery approach within the existing humanitarian response. Early recovery is not a “phase,” but rather a “vital element of any effective humanitarian response.” 15 Emergency education activities should align with early recovery principles, such as school rehabilitation and system-strengthening, including continuous support to education personnel. 16 Given the prolonged nature of the conflict in Syria, it is critical to prioritize early recovery programming in education for the nearly 7 million children and education personnel in need of education support. 17

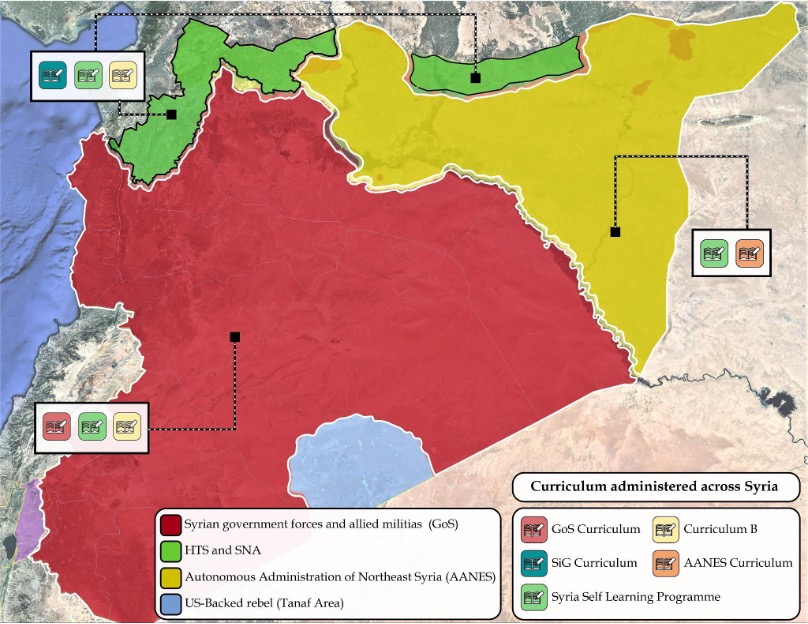

Education in Syria today includes formal 18 and non-formal education. 19 Formal education facilitates learning for children ages 6 to 17 at the basic education (grades 1 to 9) and secondary level (grades 10 to 12). Additionally, there are some opportunities for early childhood education, but they are limited. 20 Harmonization and standardization of materials used for teaching and learning is a key issue across the country (see Figure 1, which maps where each curricula is reportedly used 21 ).

Due to the political fragmentation of the country, there are a number of curricula used throughout Syria today — referred to as either “formal” or “non-formal” 22 — primarily aimed at children in grades 1 to 9. Formal education, according to reports and interviews with education practitioners, refers to the curriculum of the Government of Syria (GoS), as well as a modified version 23 of it used in northwest Syria, outside of GoS control. In this report, non-formal education refers to structured, institutionalized learning that supports either a return to formal education, accelerated learning programs in order to participate in national assessments, or interventions that facilitate building technical and cross-cutting skills (ideally relevant to local job markets) for those not likely to return to formal schooling. This includes the Syria Self-Learning Program, which is a catch-up program widely adopted humanitarian actors in non-formal education centers. 24 Additionally, “Curriculum B” is an accelerated version of the GoS curriculum and is used in both non-formal learning centers 25 and formal schools. 26 Use of other remedial learning packages to support out-of-school or in-school students, developed by implementing NGOs, has also been reported. 27 Throughout areas under the de facto control of Kurdish authorities, a Kurdish and Syriac curriculum is also reportedly used in schools run by education authorities in the northeast — but not learning centers run by humanitarian actors. 28

Figure 1. Curricula administered in Syria 29

Despite a decline in active armed conflict in recent years, approximately 6.9 million Syrians have been internally displaced as of early 2022. 30 The global pandemic and the economic crisis that has emerged within Syria over the past couple of years have compounded the vulnerabilities that Syrian populations already suffered as a result of conflict and displacement. Nearly 12 million people were reported to be food insecure in 2021. 31 More than half of Syrians are estimated to be unemployed, as the value of the Syrian pound, which plummeted by more than 80%, continues to depreciate. 32 Over $4 billion in aid 33 has been requested by humanitarian actors (as part of the global U.N.-led response) to provide life-saving needs via the Whole of Syria (WoS) mechanism this year, which aims to deliver services across the country via Damascus and the cross-border response based in Gaziantep, Turkey.

Syrian children and youth continue to face enormous protection risks and bear the brunt of the conflict on every level. Over 1,400 grave violations against children were verified in 2021, 34 including nearly 300 deaths, 35 attacks on schools, and recruitment of children for combat. 36 Survivors face a shattered economy and exposure to alarming levels of child exploitation, among other protection concerns. 37 After years of ongoing conflict, only one-third of schools in Syria are fully functional. 38 Half of out-of-school children (OOSC) have never entered school, and school dropouts increase sharply after the age of 11, in particular for boys because their families need them to enter the workforce. 39 Age-appropriate learning is more out of reach than ever, especially for secondary-level youth. Additionally, the protection and security threats children and youth face in their daily journey to school puts them at further risk. 40 The education sector’s severity rankings indicate the situation and needs are highest in Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus provinces, respectively. 41 Humanitarian staff, who are also members of the crisis-affected community, continue to reiterate the importance of strong community leadership in education to combat the influence of armed actors seeking to politicize education across the country.

GoS-held Territory: GoS-held territory includes parts of Ar-Raqqah, Deir ez-Zor, Aleppo, and al-Hasakah governorates, and the entirety of Homs, Hama, Dara’a, Quneitra, As-Suwayda, Damascus, and Rural Damascus provinces. 42 The Damascus hub channels humanitarian funding to the aforementioned areas. GoS territories — constituting 67% of Syria 43 at the time of writing — have experienced less armed conflict in recent years (with the exception of clashes in the southern province of Dara’a in late 2021, 44 which impacted education in the province 45 ). However, regions under the control of the GoS have not been immune to the compounded economic challenges felt across the country, including currency devaluation and skyrocketing prices for food and essential items. Educational activities implemented through the Damascus hub mirror those in the other territories, although the key difference is the presence of the Syrian Ministry of Education (MoE) to lead and support education service delivery.

Of the regions under GoS supervision, Aleppo, Damascus, and Rural Damascus are where “catastrophic” education conditions 46 are mostly concentrated, including high student-teacher ratios (over 100 students per teacher) and long, often unsafe, journeys to schools. 47 The highest severity rankings signify high dropout rates and limited return to learning post-initial COVID-19 closures. Additionally, age-appropriate education opportunities for youth and children with disabilities (CWDs) are extremely limited. 48 One aid worker based in the Damascus hub said that economic sanctions levied by the U.S. and European countries have impacted the country’s youth education programming, with agencies reporting difficulties in obtaining materials and equipment for skills and vocational programs. Additionally, non-formal educational programs have been difficult to implement, as some online learning platforms and websites are inaccessible in Syria due to sanctions. Although the U.S. and the EU have endeavored to provide humanitarian exceptions to sanctions and remain the largest providers of aid to Syria, aid organizations have reported limited options for procurement and banking restrictions due to directly sanctioned entities, as well as overcompliance that stems from fear of doing business with potential targets of sanctions.

Coordination in areas under different authorities also poses challenges. The provinces of Deir ez-Zor and al-Hasakeh have territory both in and out of GoS control, which have high rates of OOSC and severe accessibility challenges for implementing actors; different authorities further contributes to the lack of harmonization and resources needed to deliver quality, relevant education. 49 Finally, in terms of teacher salaries, unlike other territories of Syria, incentives are reportedly paid on a regular basis to teachers; however, incentives are lowest in GoS-territory, at approximately $35 per month. 50

Northwest Syria (NWS): NWS response includes Idlib Province and parts of northern Aleppo. NWS is characterized by a heavy presence of armed actors with varying levels of interest and ability to impose their authority on education service delivery by humanitarian actors. 51 This includes a plethora of rebel groups and armed factions, including Hay’at-Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the al-Qaeda offshoot in Idlib. Part of the northern Aleppo Governorate, west of the Euphrates (northern Aleppo countryside), remains under the direct military control of the Government of Turkey (GoT) and its supporting factions. The latest findings 52 report that children in NWS face more devastating risks and violations of their rights than in any other part of the country, including attacks on schools, recruitment of children into armed groups, child labor, and exploitation. 53 Aleppo and Idlib are the two governorates with the highest needs based on the sector’s severity ranking. In the NWS response, there are over 800,000 OOSC, a number that has grown by nearly 40% since 2019 54 due to increased displacement resulting from armed conflict and deplorable economic conditions. The dearth of livelihood opportunities, compounded by the country’s economic crisis, continues to play a major role in school-age children and youth whose access to formal or non-formal education has substantially diminished, thus increasing their exposure to negative coping mechanisms. 55

Parents who are unable to secure consistent access to income face immense pressure to send their children to work or marry them off before the age of 18. 56 Beyond the challenges external to education, there are reports that teachers have not been paid 57 for nearly two years. 58 Moreover, at different stages in the crisis, teachers in the north of the country have been compelled to travel to GoS-held territory to collect their monthly salaries as public sector employees, although this has become increasingly rare. 59 A lack of age-appropriate schools has also contributed to high rates of OOSC in NWS. 60 Secondary education services have been largely underfunded, including incentives for secondary-level teachers and funding to support facilitating secondary-level examination in GoS-territory for learners in NWS. 61 It is also important to note that the areas of NWS under the supervision of Turkish forces have limited funding partly due to a lack of appetite from donors to prioritize this contentious geographical area. 62 The GoT does implement some education interventions, including providing support to schools delivering the curriculum known as the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) curriculum. 63

Interviews conducted for this report revealed that the criteria for what key donors are willing to fund in education in NWS continues to narrow. For example, one key donor that funds almost half of learning facilities in NWS does not fund education activities beyond grade 4, leaving lower and upper-secondary level learning activities severely under-funded. 64

Territory under the Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria (AANES): AANES includes most of Ar-Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, and al-Hasakah governorates, with territory under the supervision of the GoS in each. 65 The security situation in AANES remains unstable. Reports of intercommunal violence in several camps, including al-Hol and others, have increased in early 2022. 66 Unlike the humanitarian response from the NWS and GoS-territory, North East Syria (NES) no longer has a U.N.-mandated cross-border mechanism or official U.N. presence. 67 Therefore, a group of international and Syrian NGOs has taken over the coordination of the humanitarian response under the umbrella of the NES NGO Forum, including Sector Working Groups such as the Education Working Group. The region faces complexities in accessing aid and inclusion of its needs in key national documents, such as the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). 68

NES is characterized by large pockets of OOSC, with oversaturation of education service delivery in some formal camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) using catch-up curriculum, while other informal settlements remain under-serviced. 69 Several of the country’s largest IDP camps are located within this region. Approximately 1.4 million children and youth are in need of education services in AANES. 70 The various curricula taught (see Figure 1) designate the language of instruction for learners in AANES. As with NWS, lack of age-appropriate learning opportunities in NES has contributed to high rates of OOSC. 71 Activities using a catch-up curriculum are administered in English and Arabic, but authorities in AANES implement their own curricula in Kurdish 72 as well as in the Syriac language. 73 There is anecdotal evidence that administering Kurdish curricula in AANES has pushed some parents to move to the GoS-held part of al-Hasakah province in order to access the recognized, Arabic-language GoS curricula. 74 This issue has been echoed in other reports and will likely continue based on the quality of education services delivered in AANES. 75

The sporadic location of formal and informal camps and settlements has made it challenging for education service providers, who are often based in the central al-Hasakah Governorate, to properly assess needs and deliver services in these pockets. 76 While the NES hub participates in the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)-led country-wide HRP, it is not eligible for pooled funds managed by OCHA due to the exclusion of the NES from the U.N. Security Council cross-border resolution. Therefore, funds for the response plan are granted via bilateral funding to NGOs registered in AANES, substantially limiting the available funding and range of options for other NGOs.

While curricula and quality of teaching and learning should be prioritized by donors, AANES education actors interviewed for this report shared that the immediate priority is to significantly reduce the number of OOSC through outreach and improved access, and increase children and youth participation in catch-up programs for eventual transition to formal learning. 77